Being his own client offered Philip the opportunity to push boundaries –

combining wisdom earned designing houses with SAOTA over the years

with something a bit more whimsical and experimental. “When architects

design their own homes,” he says, “they can have a bit more fun; they can be

a little bit less intellectual”.

That doesn’t mean that the design of his own home is any less rigorously

thought-out, but rather that Philip could take the opportunity to explore

architectural ideas without necessarily feeling the need to present a definitive statement or conclusive theory and weave in personal associations and

preferences.

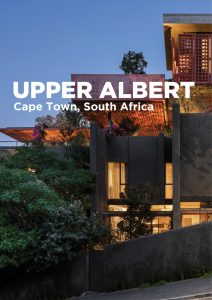

The corner site he secured was steep and had an “unmemorable” 60s ranch

style house in the centre of a large garden, as was typical of the garden

suburbs of the era. Philip points out, however, that the City of Cape Town’s

densification strategy in this area presented new possibilities. In response, he

subdivided the property along a contour and redeveloped it to create a five-bedroom family home on the upper section and two four-bedroom rental apartments on the lower.

“The objective was to create a single house that enjoyed the

activity and the energy of the city,” says Philip. At the same

time, he sought to recreate something of the spirit of a single

standalone house in a garden suburb for a changed urban

context.

Conceptually, the relationship between the main house and the

accommodation below, separated by a shared wall, references

the row houses that historically characterise the area. When it

came to designing the main house, however, instead of a garden

on the ground level, Philip extended the footprint of the house

right out to the setbacks to create a podium on the lower two

levels. “I wanted to build my garden up in the sky,” he says.

The podium includes garages with a gym, guest and staff accommodation, and utility rooms.

The upper two levels are

dedicated to the living space, which, from that height,

can take maximum advantage of the spectacular views

of the city. The third level accommodates the living area

and a covered outdoor terrace. Four ensuite bedrooms

plus a small lounge and study occupy the uppermost

level, including a generous office for Philip and a yoga

studio for his wife.

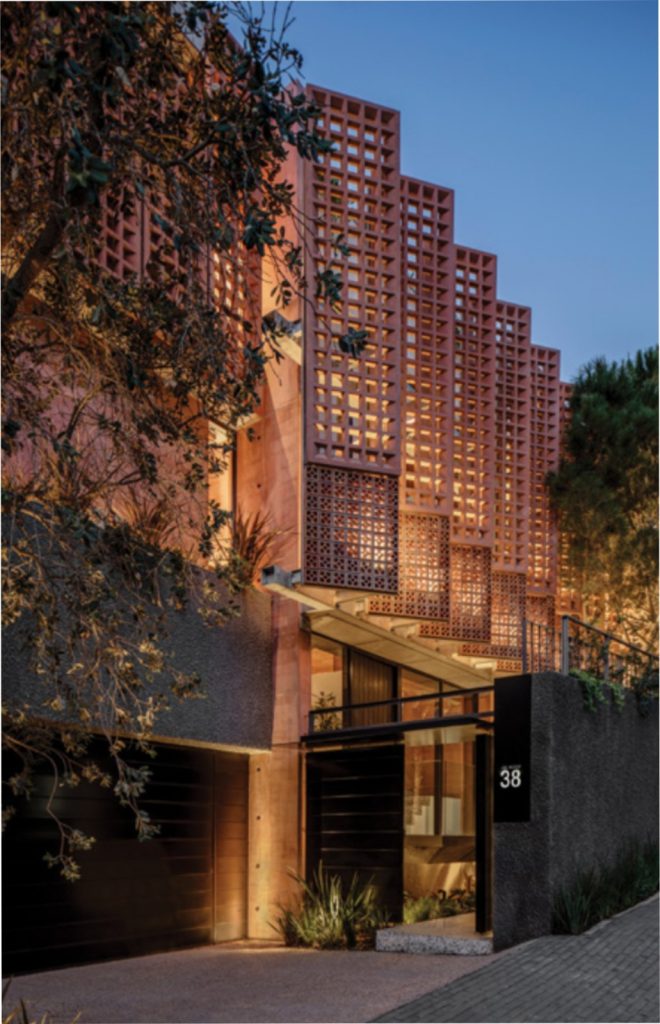

From the street, the boundary walls and plinth are

finished in grey stipple plaster, which is a reference to

Cape Town’s mid-century residential buildings and is also

associated with the campus of the University of Cape

Town and its prominent place in the city’s architectural

heritage.

However, the building’s primary identity is imparted by the

distinctive red-pigmented off-shutter concrete of the

upper levels, especially the angled pre-cast concrete

screens mounted on steel frames, which provide shading

and privacy for the extensive façade glazing. The choice of

colour, Philip says, was partly based on memories of a trip

he and his family took to Mexico. He also, however, repurposed terracotta breezeblocks that formed part of the old boundary wall, which, he says, were “removed, stored,

sandblasted, brought back and built into the structural

steel screen”.

The colour, however, also expresses and emphasises the

raw materiality and texture of the concrete. Philip says that

he, like a lot of architects, “loves the way things are built”,

and something of that fascination and delight is built into

the tactile use of materials and expressive tectonic

elements of the facade.

Internally, the character of the house is best exemplified by

the main living space, which has been conceptualised as a

single, large, open-plan area that takes in the living room,

kitchen and dining rooms. These constitute a series of

overlapping, interconnected spaces, which is a distinctive feature of a SAOTA-designed homes, forming a flowing platform for living.

Philip says that the “contrast of crisp lines, clean

geometries and tactile finishes” is central to SAOTA’s

approach – “the idea of combining contemporary

design with natural materials to create an architecturally progressive space that is also a comfortable and

happy space to live in”.

Lighting, too, is fundamental to the experience of the

living space: “The whole upper level is characterised

by soft light,” says Philip. The screens, of course, filter

the light, but skylights, south-facing clerestories,

which let in a light that is “moderate and beautiful,”

and even high windows in the stairwell, which catch

the late afternoon light, are thoughtfully positioned.

While artificial lighting is unnecessary during the day,

at night, Philip has been sure that light falls in “warm

pockets” to “create interest” and variance, often

employing freestanding lights.

The seamless fusion of the interior and exterior

spaces, separated only by floor-to-ceiling glass

sliding doors that disappear completely when

opened, impart a palpable sense of place. As Philip

says, SAOTA’s most successful living spaces are

those in which the connection between interior and

exterior space is direct and uncomplicated.

The garden itself, however, includes “beautiful little

pockets of space framed by landscaping”. Philip says

he “absolutely loves” Spanish architect Ricardo

Bofill’s famous house built in a converted cement

factory. He’s always been enchanted by its simple,

generous, flowing spaces, raw materiality and the

way in which “the landscaping seems to invade the

building”. The wild, overgrown character of the landscaping of Philip’s own home constitutes a vision of

the happy co-existence of architectural and organic

elements.

The interiors introduce a new dimension of complexity and interest to Philip’s engagement with materials,

often including extensive research and development,

innovation and collaboration. The materials he’s

chosen for the interior finishes introduce a thoughtful

dialogue with the living heritage inherent in the skills

of artisans and craftsmen. The polished polymer

concrete floor, for example, used extensively over the

living room, floors, staircases and exterior paving, is

made with a green stone aggregate that is a byproduct from the historic copper mines in the Namaqualand area in the

Western Cape. Rustenburg granite is used for paving in some areas,

and local sandstone pavers around the pool and the dining outdoor

dining area.

Solid stone features prominently in furniture pieces, too. Paarl granite, for example, was used for the striking four-piece server in the

living room, a console in the master bedroom and the basins, all crafted by JA Clift, a third-generation stone mason in Paarl known for

their work on the Afrikaans Language Monument.

Other heritage finishes referencing the 50s and 60s include the

hessian wall. The timber lattice ceiling design (a lightly stained locally

hardwood, Meranti, which complements the cast concrete screening)

adds richness and a sense of continuity between inside and out.

Other elements are more “quirky” or sentimental. “The breakfast

counter in the kitchen was the old dining table,” says Philip. “We modified it and mounted it on a stainless-steel counter.”

This fusion of this home’s exploratory engagement with materiality

and heritage, in conjunction with its bold aesthetics, proposes a creative solution to the city’s shifting urban context while making a striking addition to the suburban landscape.

UPPER ALBERT CREDITS:

Project Name

Upper Albert

Project Location

Cape Town, South Africa

Architects

SAOTA

Project Team

Riaz Ebrahim, Anthony Whittaker,

Michelle Mills, Casey Hunter

Interior Designer

ARRCC

Project Team

Mark Rielly, Nina Sierra Rubia, Anna

Katharina Schoenberger, Amy King

Structural Engineers

Moroff & Khune

Quantity Surveyor

Meyer Summersgill

Main Contractor

Red Sky Projects

Lighting Consultant

Martin Doller Design

Landscaping

Reto Mani Garden Services

Project Photographer

Adam Letch

Text by

Graham Wood